Effectively, Hannibal’s war against Romans destroyed the original Roman coinage system. But these financial strategies failed to produce the intended monetary gains. In an effort to raise money, the Roman leaders devalued their existing coinage system: they struck gold coins, debased silver coins, and reduced weight standards. The existing Roman monetary system suffered because of the heavy financial strains brought on by war. Standardization of the coinage system and monetarizing of the society quickly changed during the Second Punic War (218–201 BC), when Romans battled Carthage for supremacy in the Mediterranean basin. Instead, they intermixed local coinage systems with their own unregulated and rather unsystematized coinage types. In essence, the Romans did not have a pervasive and workable coinage system. For example, the military was not paid in coins, but in kind or through the spoils captured in conquest. Nevertheless, at this early period, the Roman economy was still only partially monetarized.

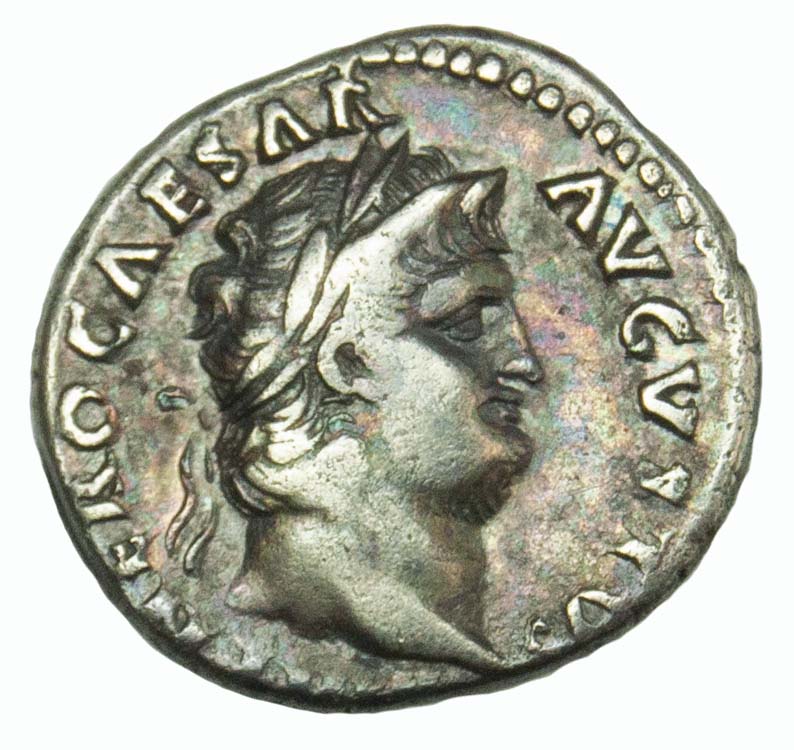

This system consisted of four original independent units, large bronze bars, struck silver coins, struck bronze coins, and large bronze discs, all of which became somewhat systematized and interrelated around 250 BC. Though coins were not unknown on the Italian peninsula between 900 BC and 300 BC, most numismatists of Roman coinage date the origins of the Roman coinage system to approximately 300 BC. Brief History of the Origin of the Denarius In order to magnify the meaning of the parable in our modern day, this research note will answer the questions: What was a denarius? How much was it worth? Was the denarius a daily wage? The answers to these questions helps us contextualize the value, amount, or the relative significance of the debt these two servants carried and helps us to clarify the parable’s significance and application for our own lives. In doing so, Jesus hopes Simon will recognize his error and empathize more fully with the sinful woman as she rejoices in the forgiveness of her overpowering debt. To castigate Simon’s lack of charity and to highlight why Jesus’s forgiveness of the woman meant more to her than the same forgiveness might mean to Simon, Jesus tells the parable of two debtors. 1 Jesus shares this parable with Simon the Pharisee, who had expressed distaste for Jesus’s having his feet washed by a sinful woman. These two contrasted servants represent the readers or listeners. The three characters are (1) a lord or master, or in this instance a creditor, who represents the Lord (2) a servant in debt to the lord for 500 denarii and (3) another servant in debt for 50 denarii.

This is a three-point parable, with three main characters, each representing a lesson to derive from the story. The parable of the two debtors in Luke 7:40–43 poses a scenario of contrast between two servants, each in debt to a creditor. Though we cannot with accuracy make the claim that a Roman denarius was always the daily wage, we can determine that the debtors of Jesus’s parable owed something on the order of a year’s worth of wages and ten years’ worth of wages. Abstract: This note provides a brief overview of Roman economic history and currency in order to throw light on the value and significance of the two debts illustratively used by Jesus in his parable to Simon the Pharisee.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)